How to Change a Belief System

Upbringing and My Past Life

Growing up in a working-class suburb of Melbourne, I used to be quite the opinionated kid.

I put this down to childhood insecurities, a false sense of superiority and the culture I was indoctrinated into telling me to stand up for what I believe in — not an altogether unhealthy ideal if exercised properly — and to say discourse-denying things like “that’s my opinion and I’m entitled to it”.

I was raised as a first generation Australian, the son of ethnic Macedonian migrants who had moved to Australia from the former Yugoslavia, and so naturally, my head was filled with belief systems pertaining to religion (Orthodox Christian) and Macedonian nationalism, that had me beating my chest and waving many a flag until my mid 20s.

I used to take an attack on an opinion or belief of mine as a personal attack and promptly got defensive and militant.

Today, I’m more or less an atheist, although I don’t like putting labels on things. I’m still proud of my Macedonian roots, but I’m no nationalist, and I’m under no illusion that my brethren are any better than the rest of humanity — a ridiculous sentiment that many children from different ethnic backgrounds are indoctrinated into all over the world — especially not when you consider the country’s economic realities, or its intellectual, athletic and cultural contributions to the world, which are few and far between.

Clearly, I was indoctrinated into more than just political beliefs — like wearing my sister’s 80s getup

Today, I wave a proverbial flag for humanity, and every four years you might see me waving an actual flag — that of Australia’s at the FIFA World Cup — and promptly putting it away at the end of the group stage.

Having been proven wrong about my beliefs so many times over the years, I echo veteran-VC Marc Andreesen’s philosophy and keep strong opinions, weakly held.

Changes…

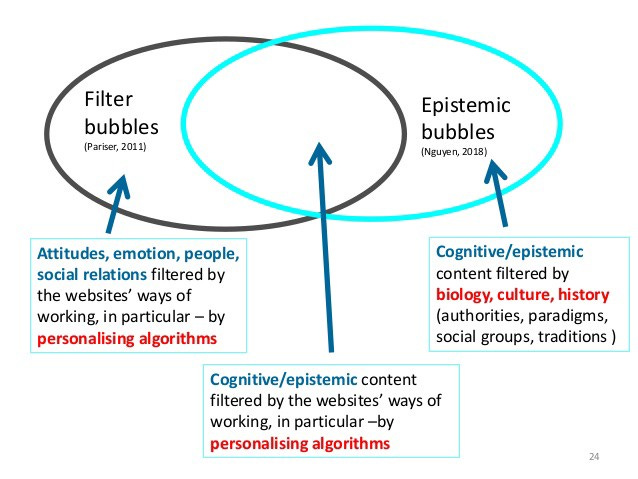

As C Thi Nguyen posited, “members of epistemic bubbles merely lack exposure to relevant information and arguments…members of echo chambers, on the other hand, have been brought to systematically distrust all outside sources”.

In my case, it was a matter of not having enough exposure to relevant information and outside arguments. I also used to be a lot more ego-driven, less contemplative and I lacked any sense of self-awareness.

So what changed?

Eight years ago, after almost a decade of what I call being comfortably miserable in the corporate world, I legged it for a shot at entrepreneurship — to earn my freedom, validate my ego and hopefully make some money.

I got a lot more than I bargained for.

Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

Entrepreneurship

In order to give myself the best chance of success, I visited my local bookstore and picked up a number of entrepreneurship and business books — this included Tim Ferriss’ 4-Hour Work Week and Eric Ries’ The Lean Startup.

I learned that 95% of startups fail, and usually, because of market failure— taking products to market that were based on flawed assumptions about what the market wanted.

I learned that the best way to learn what the market wants is to define your assumptions, and find fast, cheap, low-fidelity ways to test those assumptions.

Psychology

Next, as I started to gain some traction in my business, I picked up books on psychology so that I could become better at leading and selling.

This took me down various rabbit holes and I discovered, among other great books, Daniel Kahneman's Thinking Fast and Slow, Robert Sapolsky’s Behave and I also read Tim Urban’s write-up on the brain.

Ultimately, I learned that we only have so much agency over our thoughts and decisions and that what we think and do is a by-product of many things, including evolutionary programming that can bias us towards fight or flight, fetal conditioning, infancy and upbringing, past experience, societal conditioning, our environment, and even bacterial diversity in our guts.

I also learned about the numerous cognitive biases that serve to influence our thinking — for better or for worse — such as anchoring, the recency bias, the fundamental attribution error, the availability bias, the negativity bias, and 31 other biases I captured in this Medium post.

This also served to give me a great sense of self-awareness.

Philosophy

Wanting to become a better decision maker — in both my business and my life — required me to first regulate my emotions, and then obtain some guiding principles that would help me move forward, without falling victim to the lowest hanging fruit bias, otherwise known as instant gratification.

Socrates

So I sought out philosophy and became familiar with thinkers like Socrates, Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, Epictetus, Plato, and numerous others. One of the key ideas I took from this was that of Socratic thought, and the idea that the more you know, the more you realize you know nothing — something I was becoming painfully aware of the more content I consumed on myriad topics.

Conversations with Giants

I launched the Future Squared podcast in January if 2016 and it’s now over 340 episodes young.

It has given me the opportunity to stand on the shoulders of giants by speaking with them — I’ve been fortunate enough to speak with the likes of Tyler Cowen, Robert Greene, Kevin Kelly, Gretchen Rubin, Annie Duke, Adam Grant, Brad Feld, Tim Harford, Steve Blank, Andreas Antonopoulos, and too many more to mention.

These conversations have taught me many things, including:

Black Swan events

For Centuries, the term black swan was almost synonymous with flying pigs — it was used to signal the impossible. The term itself was derived from the Latin expression ‘“’rara avis in terris nigroque simillima cygno‘”’ (a rare bird in the lands and very much like a black swan).

However, in 1697, Dutch explorers discovered actual black swans in Western Australia. The term ‘black swan’ had morphed to represent the eventual disproving of rock-solid ideas based on the emergence of new evidence.

Never rule out the probability of a black swan event.

2. The replication problem in the social sciences

It’s probably not surprising that self-proclaimed skeptic, Michael Shermer, would tell me that “we’re wrong about most of our ideas most of the time” , but he also introduced me to the replication crisis in the social sciences, and that something to the order of 50% of studies, many foundational, cannot be replicated.

This speaks volumes of the role of confirmation bias, and the fact that data is only as good as the data you use, and how you choose to interpret it — often, the same data can be manipulated to tell many contradictory stories.

So, just because you read about it in a study it doesn’t mean it’s true.

Science doesn’t always show us whether a hypothesis is true or not; sometimes it just shows us how good a scientist is at creating the conditions for the hypothesis to be proven true.

Shermer also riffed on the narrative fallacy — the fact that we have a limited ability to look at sequences of facts without weaving an explanation into them, or, equivalently, forcing a logical link, an arrow of relationship upon them when there is none.

This is a hallmark of most business books out there, that try to explain why a company performed or didn’t, after the fact. Interestingly, four out of the eleven companies profiled in Jim Collins’ classic Good To Great have been de-listed.

Good to Great, Jim Collins

As Shermer said, “it’s much easier to postdict rather than predict”.

3. A conversation with Annie Duke on believable managers

Former World Series of Poker champion, Annie Duke, pointed out the following.

Take two managers.

Manager A is 100% confident about their decision — just because.

Manager B is 70% confident and explains why they’re at 70% and what they’re unsure about.

Who do you believe?

Most people trust Manager B.

It’s likely that Manager A is suffering from insecurity, imposter syndrome and rather than risk showing their team that they don’t hve all the answers — a trait of people with high emotional intelligence — they claim they know with full 100% confidence what to do.

I’d rather be Manager B.

4. A fast-track to moral righteousness

Robert Greene, author of the 48 Laws of Power and Mastery, said that when people believe too strongly in an idea or cause, and see things in black and white, they’re likely looking for a fast-track to moral righteousness without doing the work. They are probably deriving a sense of identity from aligning themselves with the cause. An empty barrel makes the most noise.

Empty barrels make the most noise.

As Adam Grant says, if you’re arguing with someone and you ask them “what evidence would change your mind?” and they say “no evidence”, then stop. You can’t reason with the unreasonable.

Today, there are many unreasonable people in influential places, so one must be extra careful when it comes to what they read on the internet — or anywhere for that matter.

5. Experts contradicting other experts

Funnily enough, many of the so-called experts on my podcast contradict other experts from the same domain.

So it becomes painfully clear that nobody knows for sure what’s going on — people, and experts, only have different degrees of understanding.

A Long Journey

All of these aforementioned factors — and more — essentially coalesced over a period of eight years, to expand and change my world view dramatically.

Nowadays, I question most things, I consider the counterfactual, I steer clear of absolute statements like “all X are Y”, and I scrutinize statistics that argue a particular point — oftentimes, it’s easy to see holes in an argument or a graph. One can manipulate graphs for example by omitting the baseline, cherry-picking data or manipulating the Y-axis.

Hell, there is a Reddit community all about deceptive graphs.

Not all that massive if you pay attention to the Y axis labels. Zoom out far enough and the difference is almost insignificant.

A scientist might conclude that people who smoke are more likely to die young. This is probably true.

However, few things in this world are attributable to a solitary cause.

What’s more likely in this case is that the smoker is probably also inclined to eat poorly, exercise sparingly, stay out late, and make all sorts of life choices that might combine to shorten their life. A scientist might also cherry-pick smokers from sociodemographic areas that are synonymous with unhealthy lifestyles.

And whatever the science says, it’s probably not true of all people — my pack a day grandfather lived until he was in his mid-80s.

As Dilbert creator, Scott Adams, says, ‘BOCTAOE — But of Course There Are Obvious Exceptions’.

Today, I welcome having my views challenged.

Rather than fight for my views to be proven ‘right’, and protect my ego, I would rather fight to learn what is right, or at least more right — based on the evidence at our disposal — so I can adjust my belief system and behaviors accordingly, and give myself the best chance of successfully navigating a complex world.

Steve Glaveski is the co-founder of Collective Campus, author of Employee to Entrepreneur and host of the Future Squared podcast. He’s a chronic autodidact, and he’s into everything from 80s metal and high-intensity workouts to attempting to surf and do standup comedy.